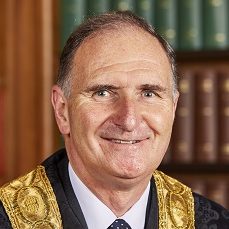

Lloyd-Jones: Disincentive to the diligent performance by solicitors of their duties

Negligent conveyancers should not be able to avoid liability because it emerges later that their client was engaged in mortgage fraud, the Supreme Court has ruled.

To do so “would be a disincentive to the diligent performance by solicitors of their duties”, it said.

Lord Lloyd-Jones said it was a matter of public policy that conveyancing solicitors “should perform their duties to their clients diligently and without negligence and that, in the event of a negligent breach of duty, those who use their services should be entitled to seek a civil remedy for the loss they have suffered”.

He continued: “To permit solicitors to escape liability for negligence in the conduct of their clients’ affairs when they discover after the event that a misrepresentation was made to a mortgagee would run entirely counter to these policies.”

While denial of a remedy may “sometimes” be justified in such circumstances, the justice said, it should only be when affording a remedy “would be legally incoherent”.

He also agreed with the observation of Lady Justice Gloster in the Court of Appeal that it was more likely that mortgage fraud would be prevented “if solicitors appreciate that they should be alive to, and question, potential irregularities in any particular transaction”.

He was giving the court’s unanimous ruling in Stoffel & Co v Grondona [2020] UKSC 42, upholding the Court of Appeal’s refusal of the appeal by the former Kent law firm, which was shut down by the Solicitors Regulation Authority in 2015.

At first instance, Her Honour Judge Walden-Smith in Central London County Court had found for Ms Grondona in her claim for damages against the solicitors for negligence and/or breach of retainer in failing to register a Land Registry transfer and a cancellation of entries for lenders form.

She awarded damages and interest of £95,000, representing the loss in value of the property.

This was even though the judge found that the claimant was a participant in an illegal mortgage fraud designed to obtain monies for a Cephas Mitchell, the purported vendor in the transaction.

Lord Lloyd-Jones rejected the law firm’s submissions that there were no potential irregularities which could have put it on notice of the possibility of fraud.

He said: “First, it is a striking feature of this case that the appellants acted for both Mitchell and the respondent, in addition to the mortgagee, Birmingham Midshires.

“Secondly, Mitchell had purchased the property in July 2002 and purported to sell it to the respondent in October 2002.

“Thirdly, the claimed value of the property had increased greatly over a short period of time. The purchase price on the sale to the respondent was £90,000, three times the price paid when the leasehold had been created three months earlier.”

The Supreme Court applied its 2016 decision in Patel v Mirza, which set out a new policy-based approach to the illegality defence at common law.

This features a three-stage test: (a) the underlying purpose of the illegality in question and whether that purpose would be enhanced by denying the claim; (b) any other relevant public policy on which denying the claim may have an impact; and (c) whether denying the claim would be a proportionate response to the illegality

While condemning and deterring mortgage fraud was obviously public policy, Lord Lloyd-Jones said he doubted that the risk they may be left without a remedy if their solicitor were negligent in registering the transaction was “most unlikely to feature” in fraudsters’ thinking; it would also deny a remedy to the lender.

The other public policies referenced in stage (b) were those relating to conveyancers.

“To permit the respondent’s claim in the particular circumstances of this case would not undermine the public policies underlying the criminalisation of mortgage fraud and could, indeed, operate in a way which would protect the interests of the victim of the fraud, ie the mortgagee.

“Furthermore, to deny the respondent’s claim would run counter to other important public policies. It would be inconsistent with the policy that the victims of solicitors’ negligence should be compensated for their loss.

“It would be a disincentive to the diligent performance by solicitors of their duties. It would also result in an incoherent contradiction given the law’s acknowledgment that an equitable property right vested in the respondent.”

This meant he did not need to consider the third stage, but he did so anyway. Ms Grondona was not looking to profit from her wrongdoing – rather it was about recovering loss caused by the negligence – and in any case, since Patel v Mirza, the question of whether the claimant profited from the illegality was relevant but not the central consideration.

This was instead the question of whether to permit recovery “would produce inconsistency damaging to the integrity of the legal system”.

Leave a Comment