Philip Martin, Internet Erasure

By Philip Martin, Senior Caseworker at Internet Erasure Ltd [1]

The Right to Be Forgotten allows private individuals to ask search engines, for example Google or Bing, and AI platforms, e.g. ChatGPT, to remove articles and images from results (delist) when their name is searched in the UK and EU.

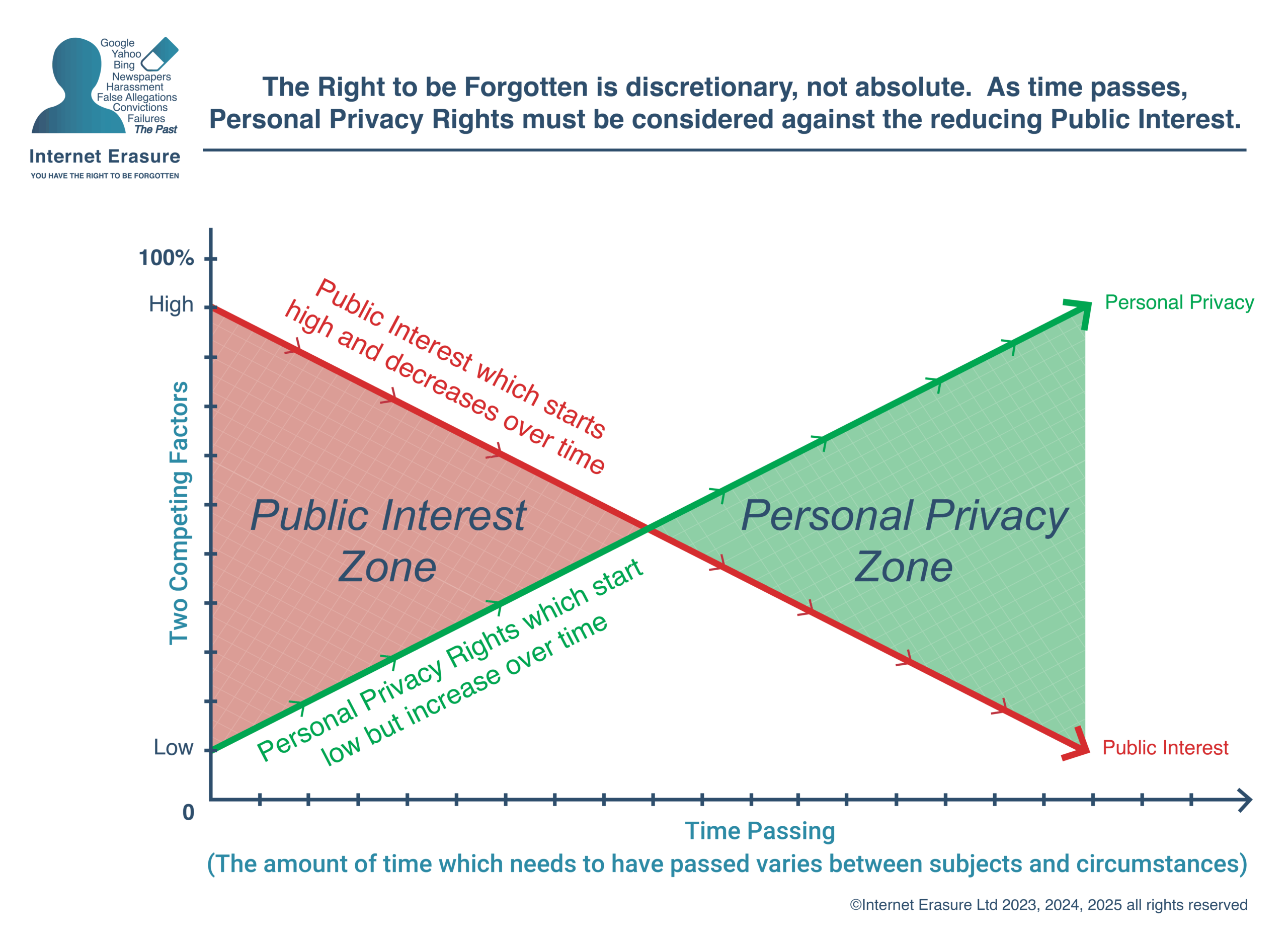

The Right to be Forgotten is not automatic; each case is argued and considered by performing a balancing test between personal privacy and public interest. This is an area of discretionary and subjective rights without absolute rules.

The legal foundation of the Right to Be Forgotten sits within Article 17 UK GDPR (Right to Erasure) and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (Right to Privacy), incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998.

These provisions are interpreted through landmark cases such as Google Spain SL & Google Inc v AEPD and Mario Costeja González (C-131/12), which first confirmed that search engines are data controllers responsible for delisting requests, and the UK decision NT1 & NT2 v Google LLC [2018] EWHC 799 (QB), which refined how UK courts balance privacy rights against freedom of expression.

Together they form the framework used by search engines, regulators, and courts to decide whether continued indexing of personal information remains lawful and proportionate under UK GDPR.

In practice, the biggest factor which affects eligibility for removal is the amount of TIME that has elapsed since the events and publication.

Public interest begins high, especially for criminal, regulatory, or safety matters, but except in extreme cases such as life sentences for murder, it usually reduces as time passes.

At the same time, the right to rebuild private life strengthens, forming the Personal Privacy Zone.

We use a simple visual to demonstrate this.

The Public Interest Zone dominates immediately after an event, when open justice, public awareness and accountability are vital. The Personal Privacy Zone grows over time as relevance fades. The crossover point is when privacy starts to outweigh public interest, which is when a Right to Be Forgotten request is most likely to succeed.

Examples by category showing how time can influence delisting decisions:

Minor criminal convictions

- Crossover point: completion of the full sentence, including licence, supervision, and any ancillary orders, when risk of reoffending is significantly reduced.

- Personal Privacy Zone: when the conviction is spent under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 (ROA), subject to any clear ongoing public interest, for example safeguarding.

Serious criminal convictions

- Crossover point: when the conviction becomes spent under ROA.

- Personal Privacy Zone: after an additional period without further offending, often two to five years on a case-by-case basis.

Missing-person cases

- Crossover point: when the individual is found safe and well. The justification for continued presentation in search results ends.

- Personal Privacy Zone: after a reasonable period, photographs and reports become intrusive and eligible for delisting, including any later reports about the person being found.

Liquidations, bankruptcy and insolvency reports

- Crossover point: when a company isofficially dissolved and removed from the register or a personal bankruptcy has been formally discharged, marking completion of the legal process.

- Personal Privacy Zone: typically, two to five years after dissolution or discharge assuming no ongoing relevance to data subject’s professional life.

False allegations

- Crossover point: when a person is acquitted and if no retrial is planned, all the contemporaneous news reports and commentary around the allegations (however serious) become eligible for the Right to be Forgotten.

- Personal Privacy Zone: After a few months, new publicity reporting on the acquittal itself will also become eligible for removal from search engines, as the accused person begins to rebuild their life and privacy after the accusations.

Professional misconduct

- Crossover point: When all investigations are completed and any resulting sanctions or punishments have been complied with.

- Personal Privacy Zone: when around two to five years have passed since the person left the role or industry, and they are no longer operating in the same field meaning that the older coverage is no longer relevant to their current professional life.

Some matters usually remain in the Public Interest Zone: examples include

- live criminal or disciplinary proceedings,

- reporting about elected officials or other high profile public figures,

- public protection issues such as investment fraud or serious sexual offending.

Time and proportionality

Neither zone has a fixed duration. Movement from the Public Interest Zone to the Personal Privacy Zone depends on a range of factors such as relevance, seriousness, accuracy and tone, any repeat conduct, and ongoing prominence in search.

Both the Information Commissioner and Google, however, recognise the passage of time as a key factor in delisting decisions and whether continued indexing of personal data remains fair or necessary.

The Right to Be Forgotten is not about erasing history, rather it ensures that search results reflect the current reality of a person’s life.

Everyone deserves the chance to move beyond outdated information once its public purpose has expired.

As our visual shows, public interest begins high and declines, while personal privacy begins low and increases. Knowing when a case moves from the Public Interest Zone into the Personal Privacy Zone helps you judge when a request is most likely to succeed.

Internet Erasure Ltd has assisted hundreds of clients with successful delisting requests under Article 17 UK GDPR, often where outdated local media coverage continued to dominate search results years after resolution. For eligibility and free guidance, visit www.interneterasure.co.uk [2]